Sculpting Grace From Cement,

By Michael Gibson

Antibes, France

15 avril 1988

The most interesting aspect of the sculptor Claude de Soria’s work hinges on the reticence that brought it all into being.

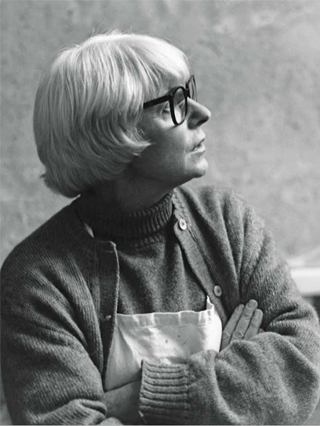

Imagine a sculptor who begins to feel nauseous at the thought of imposing some predetermined shape on her chosen material. De Soria, who studied with André Lhote, Fernand Léger and Ossip Zadkine, ran into such an apparently insuperable sculptor’s block quite early in life. The way in which she managed to overcome the obstacle offers insight into the devious paths followed by the creative process.

Basically de Soria has been playing games with chance. One work produced in 1962, at a time when she no longer wanted to work after a live model, was a 20-centimeter (8 inch) budding flower in clay. Then came an interval when she could no longer bring herself to work after any chosen subject. Finally, one evening 10 years later, when she had begun working with cement, she happened to wrap a blob of it inside a plastic bag, twisting it tightly. When she unfolded it, the dried piece of cement turned out to be a near twin of the earlier bud. She took this unexpected signal as a clue to what she should be doing as an artist : The message, in her view, was that she should let herself be guided by her material.

In the interval, there was a time when she had been unable to do more than take a handful of white potter’s clay, shaping it into a flat sheet of baked earth, marked only by hatchmarks of a wooden tool or random imprint of ther fingers and devoid of any coherent shape. Depending how you look at it, this curious vestige of a creative ordeal can, in turn, suggest a sculptural equivalent of one of Jean Fautrier’s hostages, or the desperate efforts of a child who dare not give free rein to his imagination.

In de Soria’s case, however, it would be a mistake to interpret all this as being no more than the sign of a hamstrung psyche. There is a high degree of quasi-Minimalist rigor to the process chosen by the artist, but its final effect can certainly strike one as a breakthrough since the artist ultimately managed to transfigure the banality of ordinary cement into works of supremely elegant refinement. In fact, there is a fundamental difference between de Soria’s approach and the Minimalist manner, since she is primarily concerned with the hidden life of her material.

Even her decision to work with cement was due to chance. She first tried it because a worker had left some sitting in the yard outside her studio. She picked up the malleable material one evening, plopped it down on a piece of glass and tried working on it. The cement did not retain any shape and de Soria soon gave up and went home. When she removed the cement from the glass the following morning, prying it loose with a razor blade, she was surprised and excited to discover the mottled, glossy texture on the underside of the now solid form.

In this way, she came across the two main aspects of her work : the use of that unpromising medium, cement, and the technique that consists in allowing the material she uses to dictate its conditions.

The exhibition at the Musée Picasso in Antibes (to May 2) presents an overview of 25 years of work and shows how an artist can get involved in a dialogue with a material that seems to be endowed with a willfulness of its own. In 1974, she was producing circular cement disks up to 80 centimeters in diameter. The material is pitted and marked by cloudlike patterns like Japanese “dream stones”. Over the years, other shapes followed : sphere (molded in industrially produced plastic lids), flowing drapery, and others like stakes, some of them up to 1,6 meters high.

But the most spectacular and handsome aspect of de Soria’s work began in 1985 when she first turned out pieces she designates lames and contre-lames by the French terms for a knife-blade. They are produced by pouring the cement (mixed with finely shredded packing material, which strengthens the larger works) onto a sheet of plastic that is then folded back over it until it has dried. It is the contact with the plastic that gives the cement its unpredictable gloss and pockmarks. The tallest of these reach a height of three meters; they have the pure elegance of a Chinese jade knife and they constantly surprise the artist by the fact that each comes out with a subtly different colour – some tending toward blue, others to green, red or black.

The most recent forms are like large wheels, up to a meter in diameter. Here again the outcome is dictated by the physical process that seemed to impose to itself on the artist. Unexpected folds, gaps and blotches appear in each new work and surprise her. Some items she may reject, however, because she does not like connotations that strike her as too simplistic – like the central slit, for instance, which appeared in a couple of pieces and seemed explicitly sexual.

De Soria belongs to that tribe of dreamers who are involved in a deep material reverie.

Following the almost ineffable clues that her material gives her, she manages to reveal a hidden grace that had lain dormant in a material that everyone, until then, had imagined to be graceless.